314 Life and Letters of Francis Galton

so on up to the ninth which was all black. On spinning these nine teetotums, he obtained a `real' scale of tones from white to black'. Having thus obtained a scale -of nine tones from white to black, Galton terms the fifth of these (180° painted black) the medium tone. Pictures painted with tones less than, but up to and including, the medium tone he calls `faint'; pictures painted in tones from the medium to the black, he calls `dark'. He then caused three portraits of a lady to be painted with these tones

(a) is the normal painting, using all the tones from 0 to 8, i.e. white to black ;

(b) is the faint painting, using all the tones from 0 to 4, i.e. white to medium grey;

(c) is the dark painting, using all the tones from 4 to 8, i.e. medium grey to black.

On Plate XLV will be seen Galton's scale and the portraits. Of these he writes

"I exhibit three sketches of the same portrait to show the differences of effect under these conditions, and how very little the mere question of more or less likeness is affected by them. All the tones from 0 to 8 were used in painting the first picture. Then a grey mixture that matched the medium grey was made in one corner of a palette and pure white squeezed out in another. The artist by using mixtures of this grey and white, and nothing else, made the second picture as a copy of the first. It is evident that its resemblance is not affected by the limitation of the range of tones. The third picture was made on the same principle as the second, except that black and medium grey were employed instead of white and medium grey, and here again the resemblance to the original is perfect. It follows that the value of the analytical process is not much affected by the fact that it is unable to transform, in other words that it cannot produce a transformer, or in still other words that it cannot isolate the differences between any two portraits, but only those between a light half-toned copy of the one and a dark half-toned copy of the other. It should be remarked that although the light-toned a and the dark-toned b severally contain one-half of the complete scale of tones, yet the transformer of the light-toned a into the dark-toned b contains the complete scale." (pp. 136-7).

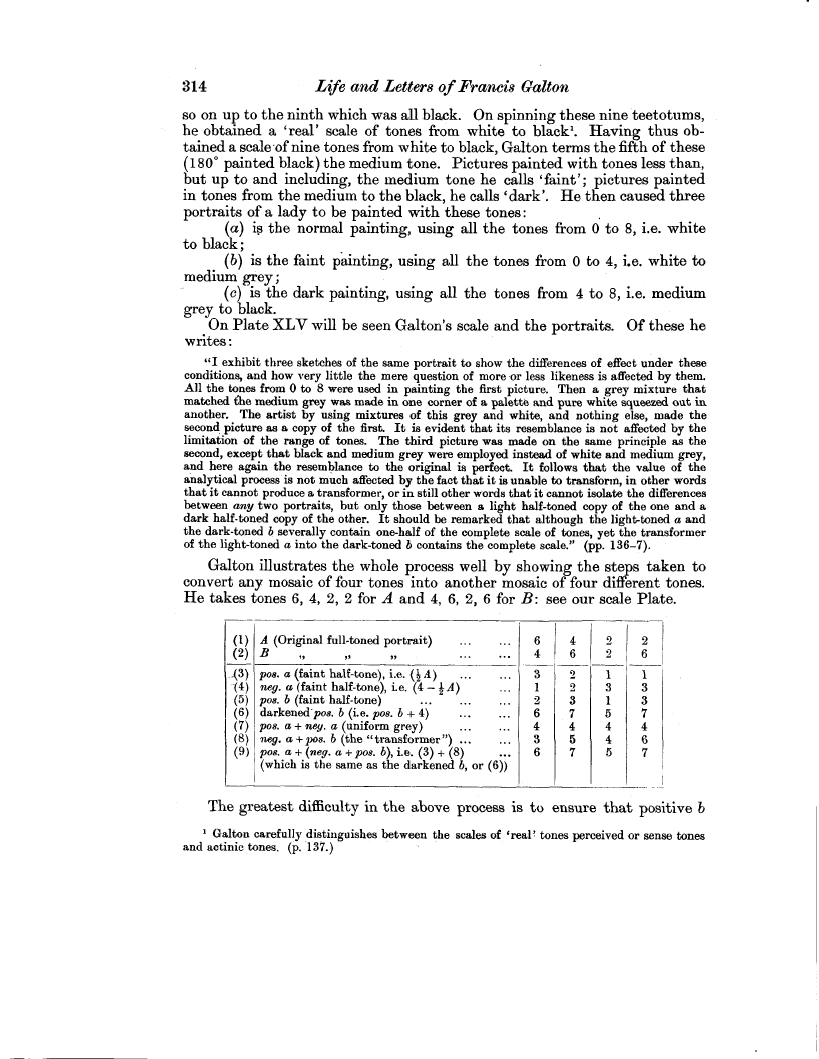

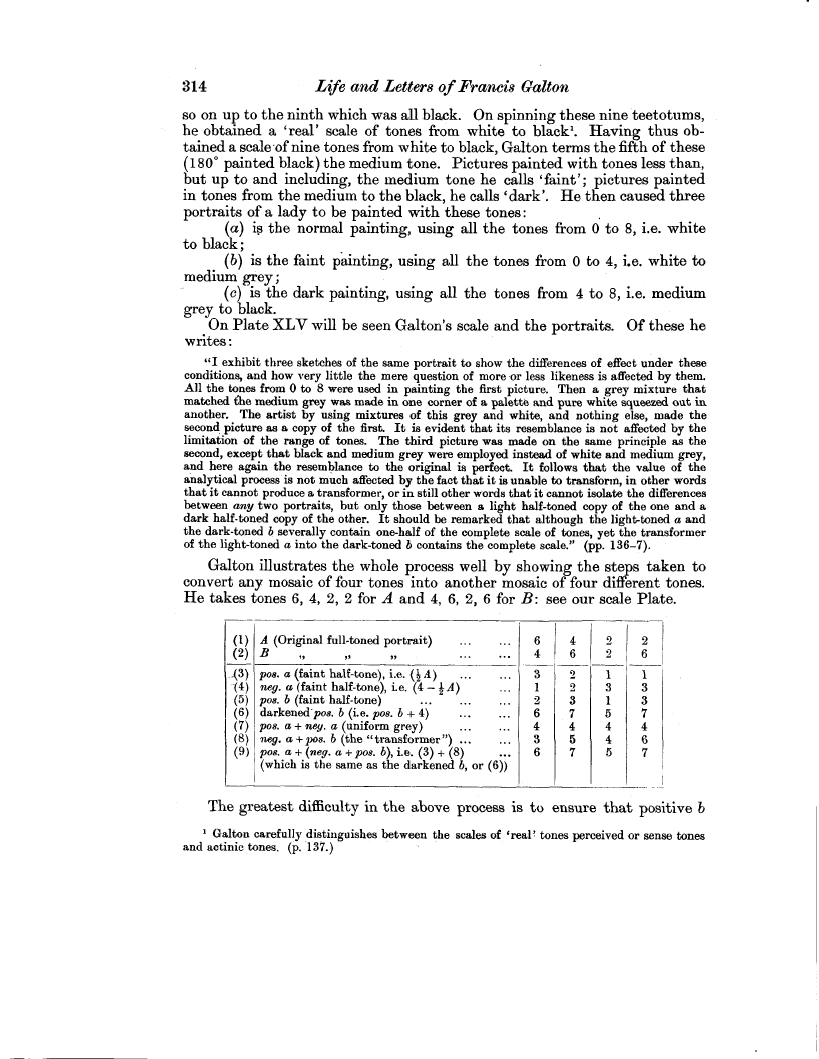

Galton illustrates the whole process well by showing the steps taken to convert any mosaic of four tones into another mosaic of four different tones. He takes tones 6, 4, 2, 2 for A and 4, 6, 2, 6 for B: see our scale Plate.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) |

A (Original full-toned portrait) ... ... |

6 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

|

(2) |

B „ „ „ ... ... |

4 |

6 |

2 |

6 |

|

(3) |

pos. a (faint half-tone), i.e. (I A) ... ... |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

-(4) |

neg. a (faint half-tone), i.e. (4 - JA) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

|

(5) |

pos. b (faint half-tone) ... ... |

2 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

|

(6) |

darkened'pos. b (i.e. pos. b + 4) ... ... |

6 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

|

(7) |

pos. a + ney. a (uniform grey) ... ... |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

(8) |

neg. a + pos. b (the "transformer ") ... ... |

3 |

5 |

4 |

6 |

|

(9) |

pos. a + (neg. a +pos. b), i.e. (3) + (8) ...

(which is the same as the darkened b, or (6)) |

6 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

The greatest difficulty in the above process is to ensure that positive b

' Galton carefully distinguishes between the scales of 'real' tones perceived or sense tones and actinic tones. (p. 137.)