106

Life and Letters of Francis Galton

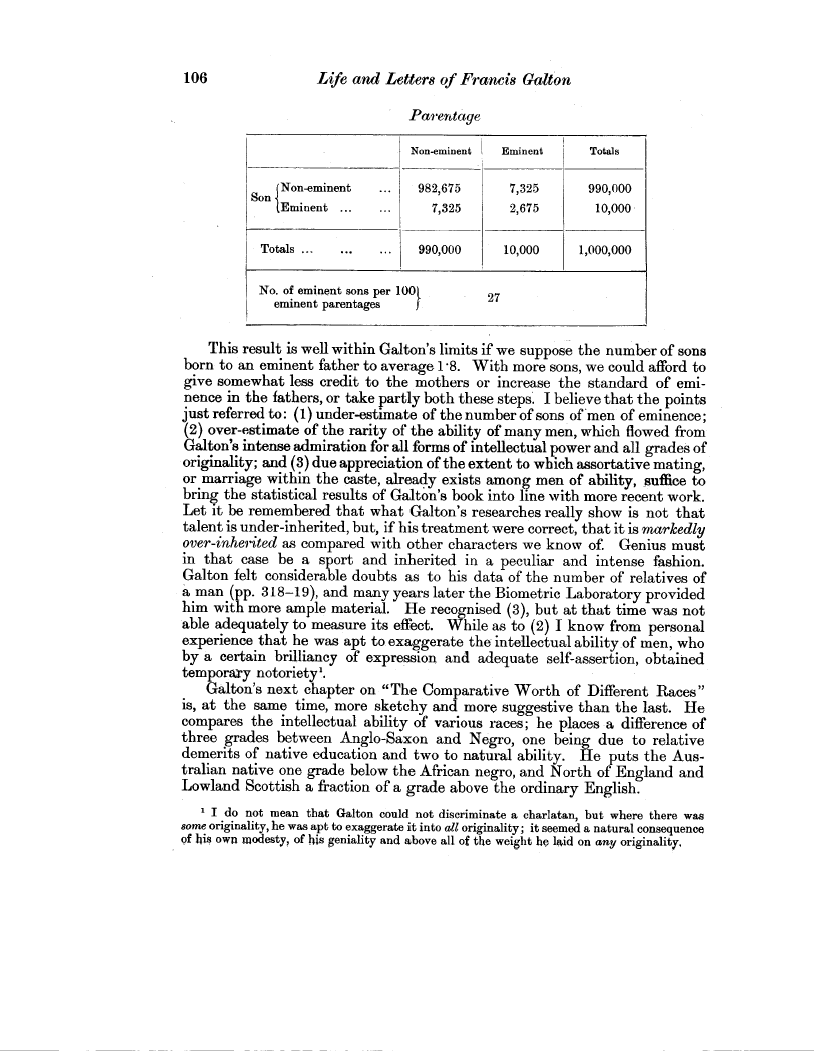

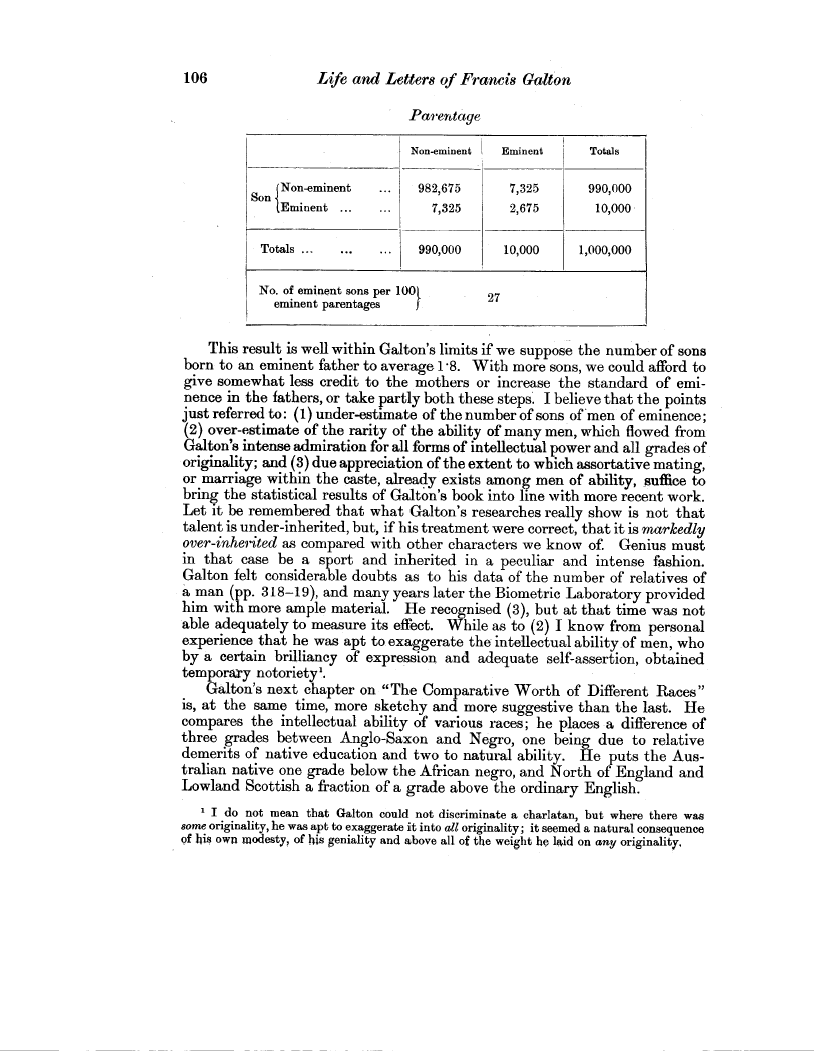

Parentage

| |

|

|

Non-eminent |

|

Eminent |

|

Totals |

| |

Son

Non-eminent

Eminent ... |

...

... |

|

982,675

7,325 |

|

7,325

2,675 |

|

990,000

10,000 |

| |

Totals ... ... |

... |

|

990,000 |

|

10,000 |

|

1,000,000 |

|

No. of eminent sons per 100 27

eminent parentages } |

|

|

This result is well within Galton's limits if we suppose the number of sons born to an eminent father to average 1.8. With more sons, we could afford to give somewhat less credit to the mothers or increase the standard of eminence in the fathers, or take partly both these steps. I believe that the points just referred to: (1) under-estimate of the number of sons of men of eminence; (2) over-estimate of the rarity of the ability of many men, which flowed from Galton's intense admiration for all forms of intellectual power and all grades of originality; and (3) due appreciation of the extent to which assortative mating, or marriage within the caste, already exists among men of ability, suffice to bring the statistical results of Galton's book into line with more recent work. Let it be remembered that what Galton's researches really show is not that talent is under-inherited, but, if his treatment were correct, that it is markedly over-inherited as compared with other characters we know of. Genius must in that case be a sport and inherited in a peculiar and intense fashion. Galton felt considerable doubts as to his data of the number of relatives of a man (pp. 318-19), and many years later the Biometric Laboratory provided him with more ample material. He recognised (3), but at that time was not able adequately to measure its effect. While as to (2) I know from personal experience that he was apt to exaggerate the intellectual ability of men, who by a certain brilliancy of expression and adequate self-assertion, obtained temporary notoriety'.

Galton's next chapter on "The Comparative Worth of Different Races" is, at the same time, more sketchy and more suggestive than the last. He compares the intellectual ability of various races; he places a difference of three grades between Anglo-Saxon and Negro, one being due to relative demerits of native education and two to natural ability. He puts the Australian native one grade below the African negro, and North of England and Lowland Scottish a fraction of a grade above the ordinary English.

1 I do not mean that Galton could not discriminate a charlatan, but where there was some originality, he was apt to exaggerate it into all originality; it seemed a natural consequence of his own modesty, of his geniality and above all of the weight he laid on any originality,